Did WW1 Make Women Harder In Heart ? (1916).

The discussion on the question "Did WW1 Make Women Harder in Heart ?" was found on the State Library of Western Australia Facebook page on 15 November, 2020. The discussion addressed the issue of how WW1 changed the 'miss' or unmarried woman.

The Facebook post was supported by commentary from an article on Trove, the database of the National Library of Australia "Has the war made women harder?", published in the Daily News newspaper on November 1916 and written by a Miss Elizabeth Ryley living through the times in London. The discussion was supported with photographs of women from the Dease Studio collection taken during the war. The post was for Remembrance Day 2020.

While a discussion of this question is way beyond the scope of a post on a blog I would like to make a record of it here. During my research about Subiaco I have found out about many inspiring women who lead independent and successful lives who did not get married. The Post Office Directors of Western Australia show that in the early 1900's many women were not married, had employment and lived independent lives in their own homes in suburbs like Subiaco, Leederville and West Perth.

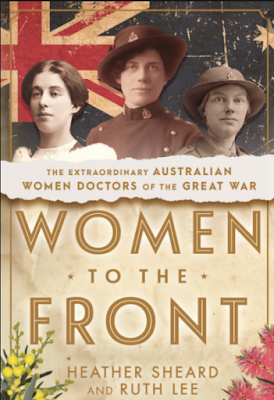

During World War 1 women including Australians who were not married left Australia and went to the front carrying out such roles as nurses and doctors. Two of these women Jessie Downie, a journalist at the Daily News newspaper who trained and served as a nurse at the front and Nurse Sister Mary Hayes who returned and ran the Subiaco Infant Health Centre also served at the front have been included on this blog because of their contribution to Subiaco.

There are a number of resources on the Internet that discuss women's roles in World War 1. The Australian Government Department of Veteran Affairs has produced a wonderful document called "Australian Women at War". "The purpose of this education resource is to provide teachers and students with self-contained classroom-ready materials and teaching strategies to explore the roles and experiences of Australian women during more than a century of conflict and peace operations. It covers all major wars and peace operations from 1899 to the present, and includes service roles as well as home front experiences..."

"Australian Women at War" states about the number of women who served at the front "...416,809 Australians enlisted in World War 1, of whom 331,781 served overseas. 61,720 of these died during the war, and 137,013 were wounded.

In all, 2139 women served with the Australian Army Nursing Service, and 130 worked with the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service. A further 423 nurses served in hospitals in Australia. Twenty-three of these women died in service during the war..."

Trove, the database at the National Library of Australia has many stories about women including nurses and doctors who served at the front. Many women both married and not married made significant contributions in difficult circumstances on the homefront leaving their traditional roles as homemakers and taking on the roles in jobs left vacant by their men who had gone to the front. They experienced the impact of war first hand rather than through the letters of their men away at the front.

The original article from the State Library is copied below. Also the article from Trove, the database of the National Library of Australia. No copyright infringement intended.

From the State Library of Western Australia Facebook page...15 November, 2020.

DID WWI MAKE WOMEN HARDER IN HEART?

Thousands of young women were left behind when their sweethearts, brothers and husbands left to serve in WWI.

While the early Victorian “miss” was a fragile young creature, "very susceptible in matters of the heart, easily fatigued and prone to fainting on the slightest provocation". The “miss” of WWI was quite different.

While “just as sweet, just as maidenly and just as attractive”, the “miss” of 1914-1918 could read their sweethearts’ letter telling of battle and bloodshed, without falling into their parents arms in a swoon. Instead going about their daily duties with an added air of pride.

Gone was the “pretty air of helplessness” of their predecessors, considered once to be such a “necessary incentive to masculine amorousness”. Gone the “docile, unquestioning obedience that marked the dutiful daughter and wife”.

But to say that the "miss" of the WWI had a “hard-cased little shell” in place of the tender heart, would be only to judge on the surface. While a new note had crept into the conversation of the average girl touched by war, this is not to say that she had become harder in heart.

Instead she had a clearer vision. An understanding that if she sent her men off with a whimpering ‘God speed’, it would only add to their burdens and anxieties.

So while she set her lips grimly to keep back the tears – she had to exert mighty self-control to keep herself from physical collapse; in short, feeling just as weak as "the most vapory of Victorian maidens".

The girl of WWI prided herself on being her man’s true and staunch comrade and while her heart ached for her particular men, she was determined to keep as cheerful as she could. Taking an interest in the progress of affairs, in the understanding that the “hydra-headed monster” (WWI) must be crushed before the world could be at peace again.

These images feature young West Australian women (1914-1918) from the State Library of WA's Dease Studio collection. Many a young woman came to the studio at 117 Barrack Street during the war years, to create a pretty portrait of herself to line a soldier's breast pocket. Indeed Mr Dease offered free portraits to soldiers prior to leaving for the war and veterans.

Like letters, photographs, became vital links to loved ones through the months or even years apart. A promise of love and stability in a life filled with uncertainty.

Today the State Library observed a minute's silence for Remembrance Day. On this day in 1918, the guns of the Western Front fell silent after four years of continuous warfare. In which time more than 330,000 Australians served and of these more than 60,000 died. Lest we forget them and all those who have served in subsequent wars.

Note - This commentary has been sourced from newspaper articles appearing in WA newspapers at the time, thanks to the magic of Trove. Namely the article - "Has the war made women harder", Daily News November 1916. It provides an insight into the event but is not intended to be a definitive history.

ABC Perth The West Australian PerthNow WAtoday.com.au Australian War Memorial Familyhistory WA - FHWA Museum of Perth Heritage Perth CWA of WA Trove National Library of Australia

Daily News, Monday 6 November 1916.

HAS THE WAR MADE WOMEN HARDER ?

According to the accounts available to-day, writes Miss Elizabeth Ryley in the 'Daily Mail,' the Early Victorian ''miss' was a fragile young creature, very susceptible in matters of the heart, easily fatigued and prone to fainting on the slightest provocation.

I wonder what she would say if she could see her great-granddaughter, the 'miss' of to-day? If she judged from the surface aspect of things great-grandmamma would undoubtedly mourn over the present-day girl's loss of feminine charm.

What has become of that pretty air of helplessness that was considered, in her day, such a necessary incentive to masculine amorousness? Where can one find that docile unquestioning obedience, that marked the dutiful daughter and wife? How is it that the 'miss' of George the Fifth's reign knows not the meaning of the word 'vapors'?

And, above all, great-grandmamma would ask herself 'with a shudder, 'How has it come about that young girls who look just as sweet, just as maidenly, just as attractive as young girls did even in my day, can read their sweethearts', letters telling of battle and bloodshed, and instead of falling into their parents' arms in a swoon can go about their daily duties with an added air of pride, and can even write to the one they love and tell him how proud they are of what he has, done? '

To great-grandmamma all this would seem to mark the very depths of unseemliness. She would decide that the girl of today possesses a hard -cased little shell in place of the tender heart that all properly constructed maidens owned in her day.

But, as I say, great-grandmamma would only be judging from the surface of things.

To the thoughtful student of human nature it certainly has been interesting to listen to the new note that has crept into the conversation of the average girl and woman since the beginning, of the war.

There will be a brightening of the eyes as some story is told of a particularly grim fight away on those battle fields abroad, followed by its aftermath of carnage. There will be intense personal pride over the deeds of their own men, even though the carrying out of such deeds involves actions which in times of peace would be verging on the barbarous.

Mothers, wives, sweethearts, sisters — something of the grim emotionalism of war has touched them all. They can visualise things that before these days of war would have made them shudder even, convincingly enough to please great-grandmamma.

But because they can visualise these things now without a shudder -at does not necessarily follow that they have become harder of heart. It means that they have become clearer of vision than their predecessors of greatgrandmamma's time. When the great sacrifice was demanded of them by their country, and they sent their men off with a whispered 'God speed,' they realised that whimpering would only add to the men's burdens and anxieties.

They felt 'feminine' enough, most of them. They had to set their lips grimly to keep back the tears— they had to exert mighty self-control to keep themselves from physical collapse; in short, they felt just as weak as the most vapory of Victorian maidens.

But in the years of their growing up —those years in which they and their menfolk had learnt to love each other— they had been enjoying a wider life than their, predecessors ever touched upon. And in that wider scheme or things they had learnt to look upon love and sentiment in a different light.

In short, they had learnt to be their man's comrade as well as his sweetheart. And no true comrade makes his friend's struggle harder than it already is if he can possibly help it.

So the girl of to-day, priding herself of being her man's true and staunch comrade, determined not to give way. She made up her mind to keep as cheerful as she could, to help others to do the same, and to take an intelligent interest in the progress of affairs so that her man should know that her thoughts and her interests were still with him.

And that, I think, is how it came about in the first instance that the women read and talked, of the war. Then, as time, went on, and the struggle assumed more gigantic proportions, they began, to see that this hydra-headed monster must be crushed for ever before the world could be at peace again.

They began to take a larger view of the whole situation. Their hearts still ached for their own particular men, but a spirit of relentlessness began to possess them. They began to see clearly that if the good and righteous cause for which our men are fighting is to be achieved it can only be by grim methods.

Their British blood was up, just as their men's British blood was up.

They watched more eagerly than before the tide of affairs. They rejoiced over our victories, their hearts were filled with pride when their own particular man did anything specially noteworthy that would help on the ultimate end. And so in time they came to take that large view of the whole struggle that has given them the capacity to read and hear of grim doings that would have taken all the courage out of the Early Victorian maiden and deprived her entirely of her self control.

All honor, then, I say, to the women who have so sternly schooled themselves to bear without flinching what in ordinary times they would not have been able to endure. It is not tenderness of heart, that they have discarded, but false sentiment.

References

Australian Government Department of Veteran Affairs (2008) 'Australian Women in War. Investigating the experiences and changing roles of Australian women in war and peace operations 1899 – Today'.

Georgraphy/History Year 9 Australian curriculum. (2014). 'Impact of war on Australian women' South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.